Allowing the environment to assert itself

The house sits opposite the island of Miyajima in the Seto Inland Sea, known as one of Japan’s “Three Great Sights”. With blue water stretching out before it and the island’s mountains beyond, the view is a privileged one, and the site is ideal, but for the constant clamor of a major highway and the railroad bed running right outside. A site appropriate to house a couple simply looking for a place to live their lives in comfort and practice their piano.

We were at first concerned that the sound outside would be a problem for the pianists, but the client was well-accustomed to the noises of the neighborhood impinging, and would be pleased just to be able to play the piano at length without disturbing others. So we set straight out to determine what we could do to make the most of the remarkable vista.

Choosing the material for the exterior shell was of utmost importance because of the damage that could be anticipated due to the constant wave of salt-sea air, as well as discoloration resulting from metal particles suffusing the ambient dust, caused by friction between the trains’ steel wheels and track. Concrete was the chosen material, therefore, and glass was mounted in a way that left no metal fittings exposed to sea air. To make it impervious to the ravages of ambient metal dust, we finished it in a rust-colored stain. Over time, the natural effect of the local dust could only serve to burnish the richness of the initial finish.

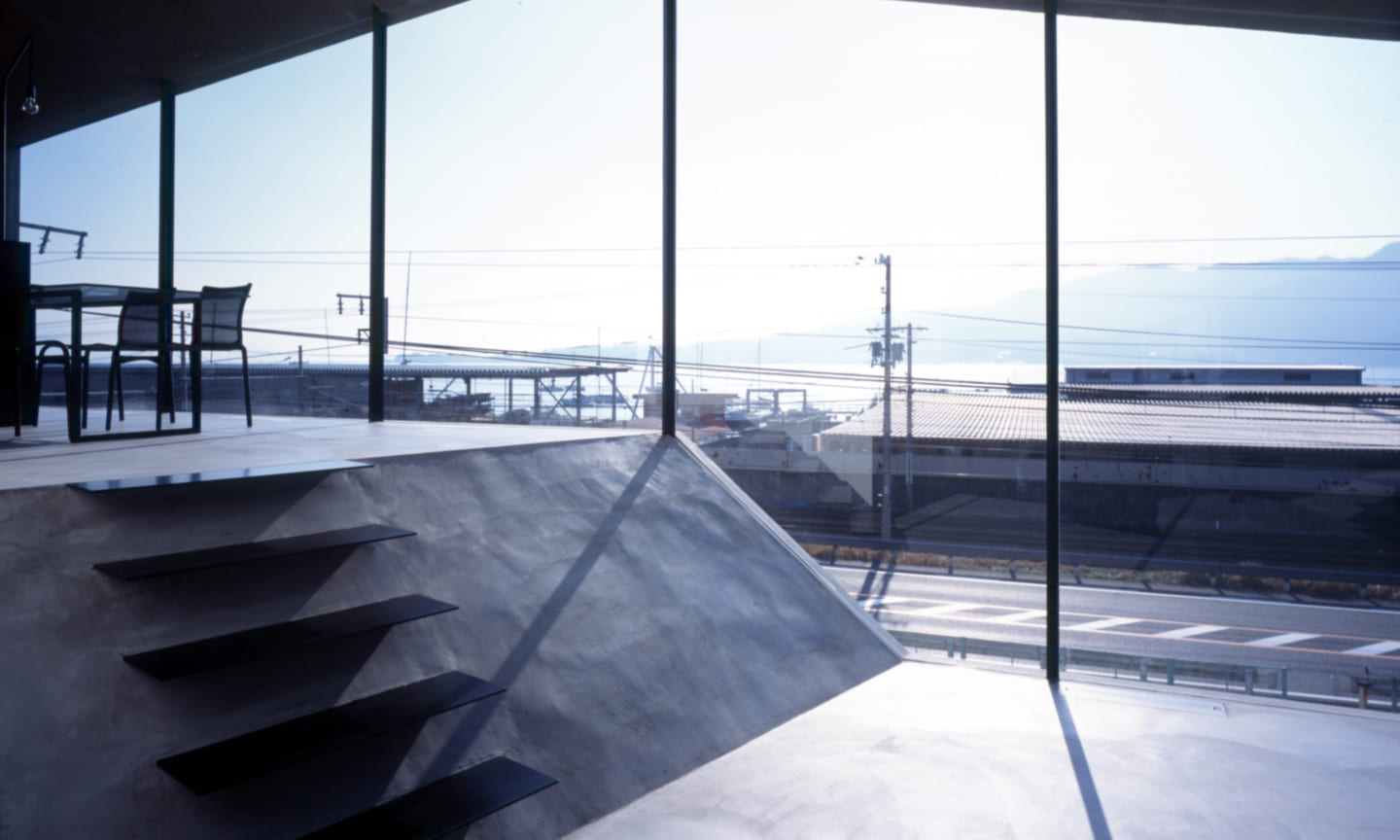

By folding a single concrete slab in the manner of origami we could span a large distance without building in excessive support, and engage a cantilever to counter the downward force of building on a sloping grade. This fold also introduced multiple levels into the house, and allowed us to offer varied, stimulating mediations of the sea view. The planar arrangement is circular, from the piano space, to the living, dining, sleeping, and water facilities. The atmosphere varies similarly, from space that is bright and active to those that grow dimmer and more restful. Matching discrete environments to their purpose and arranging them in a natural flow, we hoped, would produce a rich living experience despite this being a one-room home.

Continuous, single-platform interiors tend toward monotony, and so we created a space within which proportional differences – floor and ceiling heights, the size and shape of the window apertures – produces a perception of partitioning. We also found, incidentally, that non-parallel planes prove acoustically superior when playing the piano.

In standing up to an unwelcoming environment, the typical modern dwelling’s strategy is to employ technology and physical systems in the service of undoing the surroundings, making the building more livable, but more predictable and banal. We take a contrary approach, allowing the environment to assert itself, which both challenges and rewards the dweller with a space within which harmony can live.